Men who drink alcohol in late adolescence are more likely to develop severe liver disease decades later than young people who don’t drink at all, a Swedish study suggests.

Men who drink alcohol in late adolescence are more likely to develop severe liver disease decades later than young people who don’t drink at all, a Swedish study suggests.

Researchers examined data on alcohol consumption for 43,296 men entering military service in 1969 and 1970 when they were 18 to 20 years old. After an average follow-up of almost 38 years, a total of 383 men were diagnosed with severe liver disease, including 208 who died.

Each daily gram of alcohol men typically consumed in their youth was associated with a 2 percent increase in the risk of severe liver disease, even after researchers accounted for other independent risk factors for liver damage like obesity, smoking and cardiovascular disease.

The risk was more pronounced among heavier drinkers. Young men who typically averaged 31 to 40 grams of alcohol (equivalent to roughly 3 to 5 ounces of spirits) daily had twice the risk of liver disease as abstainers, while youth who drank 51 to 60 grams daily had more than quadruple the risk of liver disease.

“We found that most of the study subjects that eventually developed severe liver disease were previously diagnosed with alcohol abuse or dependency,” said lead study author Dr. Hannes Hagstrom of Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm.

“It is therefore reasonable to believe that drinking alcohol early in life increases the risk that you will continue to drink and might increase your intake,” Hagstrom said by email. “Also, we cannot rule out that a long duration of exposure to alcohol is a contributing cause of this increased liver disease risk.”

In the U.S., one standard drink contains 14 grams (0.6 oz) of alcohol, which is typically the amount in one 12-ounce beer, a 5-ounce glass of wine and 1.5 ounces of spirits, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

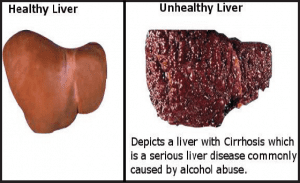

The exact amount of alcohol needed to inflict liver damage is unclear and can be influenced by other factors like what people eat, what type of alcohol they consume and how often they binge drink, researchers note in the Journal of Hepatology. But some previous research points to an increased risk of liver disease when men drink more than 30 grams of alcohol daily or when women consume more than 20 grams a day.

Overall, the young men in the current study drank an average of almost 9 grams daily. While roughly 6 percent claimed not to drink at all, almost 5 percent consumed more than 60 grams daily.

During almost four decades of follow up, 2,661 men were diagnosed with alcohol abuse, and roughly one in 10 of these men went on to develop severe liver disease.

In addition, 386 men were diagnosed with viral hepatitis and almost one in four of these men went on to develop liver disease.

The study wasn’t a controlled experiment designed to prove whether or how drinking habits early in life might cause liver disease decades later.

Other limitations include the reliance on men to accurately recall and report on their drinking habits. Heavy drinkers are also more likely than other people to use drugs, increasing their risk of catching viral hepatitis by sharing needles or other drug paraphernalia.

In addition, the researchers lacked data on binge drinking, which might impact the effect of alcohol consumption on the liver, the authors note.

Even so, the results suggest the threshold amount of alcohol linked to liver damage may be lower than previously thought, the researchers conclude.

“If or how much a person drinks in their teens is a strong predictor of alcohol use and problem drinking later in adulthood,” said Rick Grucza, a psychiatry researcher at Washington University School of Medicine in Saint Louis who wasn’t involved in the study.

“It’s quite likely that many of those who reported drinking regularly during their late teens went on to continue or escalate that habit throughout their adult life,” Grucza said by email. “In an ideal world, parents would both try to delay alcohol initiation until the late teens or early twenties and also try teach their kids to drink moderately and responsibly.”