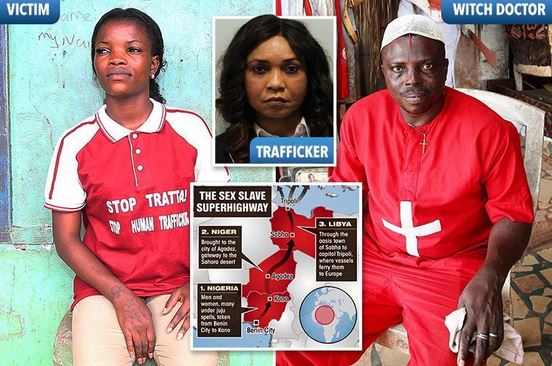

For almost two decades, 42-year-old Patience earned a steady income sending girls from Nigeria to Europe for sex work, using black magic to stop the women from fleeing. Now, she is afraid the illegal trade could kill her.

During a ceremony in March, Oba Ewuare II, leader of the historic kingdom of Benin in southern Nigeria, invoked curses on anyone who used witchcraft to aid illegal migration.

Since then, anecdotal evidence suggests the trafficking has slowed although it is too soon for firm data to be collated.

The number of female Nigerians arriving in Italy by boat surged to more than 11,000 in 2016 from 1,500 in 2014, with at least four in five forced into prostitution, according to data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

At least nine in every 10 Nigerian women trafficked to Europe come from Edo, a mostly Christian state of 3 million people, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC).

Many came through the hands of women like Patience, who supplements her income as a hairdresser by selling girls into overseas sex work – but the leader’s ceremony has stopped that.

“I didn’t hear directly from his mouth but, through the radio and television. The Oba has stopped everything,” Patience told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in her home in Benin, where she lives with her husband and four children.

“Whenever I go out, I meet girls who beg me to take them to Europe but I refuse because I don’t want to die. Everybody is afraid.”

Belief in black magic is deep-rooted in Benin, and many fear crossing their traditional leader could incur death, mental breakdown or a myriad of unexplained physical ailments.

“You don’t know what exactly the penalty (of the curse) will be. The repercussions can come in several ways,” said David Edebiri, the second highest ranking chief in Benin.

He believes the Oba’s involvement, inspired by repeated bad press in the international media, has reduced trafficking and could help bring more traffickers to justice as many women involved were too afraid of juju rituals before to testify.

“It has been very, very effective and that if even anything is going on now, it must be a very minute dimension. Not as it was before (when) it was becoming everybody’s game,” he said.

Patience said she trafficked dozens of girls to Europe over the past 16 years, paid by Nigerian brokers in Europe or madams.

The madams told Patience when they needed more girls and she then set about recruiting, usually at her salon.

Before leaving, the girls signed a deal that locked them into repaying thousands of dollars of debt. Patience then took them to a spiritual priest to seal the pact with a ritual.

Known as juju, such black magic rituals instill fear in a girl that her relatives will fall ill or die if they disobey their traffickers, go to the police or fail to pay their debts.

“My face started rotting when I refused to pay any additional money. They took me to different hospitals and conducted all sorts of tests but no one could tell what was wrong with my face,” said Florence, 24, who was trafficked to Russia at the age of 18.

Florence said she paid at least $45,000 to her madam over five years of prostitution. Then she refused to pay more.

“It was the juju that affected me,” she said, stroking her face to describe the lesions that developed a week after she defied her trafficker’s demands for more money.

But when Oba Ewuare II banned juju priests from performing any ritual to aid the human trade, its effect was instant.

“No one will ever come here again,” said David Ubebe, a juju priest who for eight years attended to a flow of women bringing girls to swear oaths at his shrine as well as phone calls from madams in Europe asking him to compel girls to pay them.

He used to earn an undisclosed income for each black magic ritual he performed, boasting his powers could make someone menstruate nonstop or lose peace of mind, but is now too nervous to defy the ban.

The dingy shrine behind his home is now quieter, strewn with animal bones and carvings. Here girls were made to eat pieces of liver – yanked from live chickens – and bits of their hair and clothing were mixed into a concoction that he made them drink.

“No one disturbs me anymore,” he said. “Even if anybody requests that I use my powers to put pressure on the girls in Europe so that they will pay, I can’t do it, because I don’t want to die.”

Nduka Nwenwene, Edo zonal commander of Nigeria’s anti-trafficking agency (NAPTIP), said victims have become more willing to testify since the Oba revoked the juju curses.

“We are seeing the impact. People who hide out or refuse to come out to give evidence in court are now coming out,” said Nwanwene who has four anti-trafficking cases pending in court, including that of Florence who, with her mother, has boldly faced her traffickers in court.

Meanwhile Patience is convinced a madam she knows in Europe has fallen ill because she defied the Oba by trying to extort more money from a girl and no one can diagnose her illness.

“It is the effect of the curse placed by the Oba on those who cheat. That is the reason why she is sick,” she said.

For almost two decades, 42-year-old Patience earned a steady income sending girls from Nigeria to Europe for sex work, using black magic to stop the women from fleeing. Now, she is afraid the illegal trade could kill her.

During a ceremony in March, Oba Ewuare II, leader of the historic kingdom of Benin in southern Nigeria, invoked curses on anyone who used witchcraft to aid illegal migration.

Since then, anecdotal evidence suggests the trafficking has slowed although it is too soon for firm data to be collated.

The number of female Nigerians arriving in Italy by boat surged to more than 11,000 in 2016 from 1,500 in 2014, with at least four in five forced into prostitution, according to data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

At least nine in every 10 Nigerian women trafficked to Europe come from Edo, a mostly Christian state of 3 million people, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC).

Many came through the hands of women like Patience, who supplements her income as a hairdresser by selling girls into overseas sex work – but the leader’s ceremony has stopped that.

“I didn’t hear directly from his mouth but, through the radio and television. The Oba has stopped everything,” Patience told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in her home in Benin, where she lives with her husband and four children.

“Whenever I go out, I meet girls who beg me to take them to Europe but I refuse because I don’t want to die. Everybody is afraid.”

Belief in black magic is deep-rooted in Benin, and many fear crossing their traditional leader could incur death, mental breakdown or a myriad of unexplained physical ailments.

“You don’t know what exactly the penalty (of the curse) will be. The repercussions can come in several ways,” said David Edebiri, the second highest ranking chief in Benin.

He believes the Oba’s involvement, inspired by repeated bad press in the international media, has reduced trafficking and could help bring more traffickers to justice as many women involved were too afraid of juju rituals before to testify.

“It has been very, very effective and that if even anything is going on now, it must be a very minute dimension. Not as it was before (when) it was becoming everybody’s game,” he said.

Patience said she trafficked dozens of girls to Europe over the past 16 years, paid by Nigerian brokers in Europe or madams.

The madams told Patience when they needed more girls and she then set about recruiting, usually at her salon.

Before leaving, the girls signed a deal that locked them into repaying thousands of dollars of debt. Patience then took them to a spiritual priest to seal the pact with a ritual.

Known as juju, such black magic rituals instill fear in a girl that her relatives will fall ill or die if they disobey their traffickers, go to the police or fail to pay their debts.

“My face started rotting when I refused to pay any additional money. They took me to different hospitals and conducted all sorts of tests but no one could tell what was wrong with my face,” said Florence, 24, who was trafficked to Russia at the age of 18.

Florence said she paid at least $45,000 to her madam over five years of prostitution. Then she refused to pay more.

“It was the juju that affected me,” she said, stroking her face to describe the lesions that developed a week after she defied her trafficker’s demands for more money.

But when Oba Ewuare II banned juju priests from performing any ritual to aid the human trade, its effect was instant.

“No one will ever come here again,” said David Ubebe, a juju priest who for eight years attended to a flow of women bringing girls to swear oaths at his shrine as well as phone calls from madams in Europe asking him to compel girls to pay them.

He used to earn an undisclosed income for each black magic ritual he performed, boasting his powers could make someone menstruate nonstop or lose peace of mind, but is now too nervous to defy the ban.

The dingy shrine behind his home is now quieter, strewn with animal bones and carvings. Here girls were made to eat pieces of liver – yanked from live chickens – and bits of their hair and clothing were mixed into a concoction that he made them drink.

“No one disturbs me anymore,” he said. “Even if anybody requests that I use my powers to put pressure on the girls in Europe so that they will pay, I can’t do it, because I don’t want to die.”

Nduka Nwenwene, Edo zonal commander of Nigeria’s anti-trafficking agency (NAPTIP), said victims have become more willing to testify since the Oba revoked the juju curses.

“We are seeing the impact. People who hide out or refuse to come out to give evidence in court are now coming out,” said Nwanwene who has four anti-trafficking cases pending in court, including that of Florence who, with her mother, has boldly faced her traffickers in court.

Meanwhile Patience is convinced a madam she knows in Europe has fallen ill because she defied the Oba by trying to extort more money from a girl and no one can diagnose her illness.

“It is the effect of the curse placed by the Oba on those who cheat. That is the reason why she is sick,” she said.

For almost two decades, 42-year-old Patience earned a steady income sending girls from Nigeria to Europe for sex work, using black magic to stop the women from fleeing. Now, she is afraid the illegal trade could kill her.

During a ceremony in March, Oba Ewuare II, leader of the historic kingdom of Benin in southern Nigeria, invoked curses on anyone who used witchcraft to aid illegal migration.

Since then, anecdotal evidence suggests the trafficking has slowed although it is too soon for firm data to be collated.

The number of female Nigerians arriving in Italy by boat surged to more than 11,000 in 2016 from 1,500 in 2014, with at least four in five forced into prostitution, according to data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

At least nine in every 10 Nigerian women trafficked to Europe come from Edo, a mostly Christian state of 3 million people, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC).

Many came through the hands of women like Patience, who supplements her income as a hairdresser by selling girls into overseas sex work – but the leader’s ceremony has stopped that.

“I didn’t hear directly from his mouth but, through the radio and television. The Oba has stopped everything,” Patience told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in her home in Benin, where she lives with her husband and four children.

“Whenever I go out, I meet girls who beg me to take them to Europe but I refuse because I don’t want to die. Everybody is afraid.”

Belief in black magic is deep-rooted in Benin, and many fear crossing their traditional leader could incur death, mental breakdown or a myriad of unexplained physical ailments.

“You don’t know what exactly the penalty (of the curse) will be. The repercussions can come in several ways,” said David Edebiri, the second highest ranking chief in Benin.

He believes the Oba’s involvement, inspired by repeated bad press in the international media, has reduced trafficking and could help bring more traffickers to justice as many women involved were too afraid of juju rituals before to testify.

“It has been very, very effective and that if even anything is going on now, it must be a very minute dimension. Not as it was before (when) it was becoming everybody’s game,” he said.

Patience said she trafficked dozens of girls to Europe over the past 16 years, paid by Nigerian brokers in Europe or madams.

The madams told Patience when they needed more girls and she then set about recruiting, usually at her salon.

Before leaving, the girls signed a deal that locked them into repaying thousands of dollars of debt. Patience then took them to a spiritual priest to seal the pact with a ritual.

Known as juju, such black magic rituals instill fear in a girl that her relatives will fall ill or die if they disobey their traffickers, go to the police or fail to pay their debts.

“My face started rotting when I refused to pay any additional money. They took me to different hospitals and conducted all sorts of tests but no one could tell what was wrong with my face,” said Florence, 24, who was trafficked to Russia at the age of 18.

Florence said she paid at least $45,000 to her madam over five years of prostitution. Then she refused to pay more.

“It was the juju that affected me,” she said, stroking her face to describe the lesions that developed a week after she defied her trafficker’s demands for more money.

But when Oba Ewuare II banned juju priests from performing any ritual to aid the human trade, its effect was instant.

“No one will ever come here again,” said David Ubebe, a juju priest who for eight years attended to a flow of women bringing girls to swear oaths at his shrine as well as phone calls from madams in Europe asking him to compel girls to pay them.

He used to earn an undisclosed income for each black magic ritual he performed, boasting his powers could make someone menstruate nonstop or lose peace of mind, but is now too nervous to defy the ban.

The dingy shrine behind his home is now quieter, strewn with animal bones and carvings. Here girls were made to eat pieces of liver – yanked from live chickens – and bits of their hair and clothing were mixed into a concoction that he made them drink.

“No one disturbs me anymore,” he said. “Even if anybody requests that I use my powers to put pressure on the girls in Europe so that they will pay, I can’t do it, because I don’t want to die.”

Nduka Nwenwene, Edo zonal commander of Nigeria’s anti-trafficking agency (NAPTIP), said victims have become more willing to testify since the Oba revoked the juju curses.

“We are seeing the impact. People who hide out or refuse to come out to give evidence in court are now coming out,” said Nwanwene who has four anti-trafficking cases pending in court, including that of Florence who, with her mother, has boldly faced her traffickers in court.

Meanwhile Patience is convinced a madam she knows in Europe has fallen ill because she defied the Oba by trying to extort more money from a girl and no one can diagnose her illness.

“It is the effect of the curse placed by the Oba on those who cheat. That is the reason why she is sick,” she said.

For almost two decades, 42-year-old Patience earned a steady income sending girls from Nigeria to Europe for sex work, using black magic to stop the women from fleeing. Now, she is afraid the illegal trade could kill her.

During a ceremony in March, Oba Ewuare II, leader of the historic kingdom of Benin in southern Nigeria, invoked curses on anyone who used witchcraft to aid illegal migration.

Since then, anecdotal evidence suggests the trafficking has slowed although it is too soon for firm data to be collated.

The number of female Nigerians arriving in Italy by boat surged to more than 11,000 in 2016 from 1,500 in 2014, with at least four in five forced into prostitution, according to data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

At least nine in every 10 Nigerian women trafficked to Europe come from Edo, a mostly Christian state of 3 million people, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC).

Many came through the hands of women like Patience, who supplements her income as a hairdresser by selling girls into overseas sex work – but the leader’s ceremony has stopped that.

“I didn’t hear directly from his mouth but, through the radio and television. The Oba has stopped everything,” Patience told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in her home in Benin, where she lives with her husband and four children.

“Whenever I go out, I meet girls who beg me to take them to Europe but I refuse because I don’t want to die. Everybody is afraid.”

Belief in black magic is deep-rooted in Benin, and many fear crossing their traditional leader could incur death, mental breakdown or a myriad of unexplained physical ailments.

“You don’t know what exactly the penalty (of the curse) will be. The repercussions can come in several ways,” said David Edebiri, the second highest ranking chief in Benin.

He believes the Oba’s involvement, inspired by repeated bad press in the international media, has reduced trafficking and could help bring more traffickers to justice as many women involved were too afraid of juju rituals before to testify.

“It has been very, very effective and that if even anything is going on now, it must be a very minute dimension. Not as it was before (when) it was becoming everybody’s game,” he said.

Patience said she trafficked dozens of girls to Europe over the past 16 years, paid by Nigerian brokers in Europe or madams.

The madams told Patience when they needed more girls and she then set about recruiting, usually at her salon.

Before leaving, the girls signed a deal that locked them into repaying thousands of dollars of debt. Patience then took them to a spiritual priest to seal the pact with a ritual.

Known as juju, such black magic rituals instill fear in a girl that her relatives will fall ill or die if they disobey their traffickers, go to the police or fail to pay their debts.

“My face started rotting when I refused to pay any additional money. They took me to different hospitals and conducted all sorts of tests but no one could tell what was wrong with my face,” said Florence, 24, who was trafficked to Russia at the age of 18.

Florence said she paid at least $45,000 to her madam over five years of prostitution. Then she refused to pay more.

“It was the juju that affected me,” she said, stroking her face to describe the lesions that developed a week after she defied her trafficker’s demands for more money.

But when Oba Ewuare II banned juju priests from performing any ritual to aid the human trade, its effect was instant.

“No one will ever come here again,” said David Ubebe, a juju priest who for eight years attended to a flow of women bringing girls to swear oaths at his shrine as well as phone calls from madams in Europe asking him to compel girls to pay them.

He used to earn an undisclosed income for each black magic ritual he performed, boasting his powers could make someone menstruate nonstop or lose peace of mind, but is now too nervous to defy the ban.

The dingy shrine behind his home is now quieter, strewn with animal bones and carvings. Here girls were made to eat pieces of liver – yanked from live chickens – and bits of their hair and clothing were mixed into a concoction that he made them drink.

“No one disturbs me anymore,” he said. “Even if anybody requests that I use my powers to put pressure on the girls in Europe so that they will pay, I can’t do it, because I don’t want to die.”

Nduka Nwenwene, Edo zonal commander of Nigeria’s anti-trafficking agency (NAPTIP), said victims have become more willing to testify since the Oba revoked the juju curses.

“We are seeing the impact. People who hide out or refuse to come out to give evidence in court are now coming out,” said Nwanwene who has four anti-trafficking cases pending in court, including that of Florence who, with her mother, has boldly faced her traffickers in court.

Meanwhile Patience is convinced a madam she knows in Europe has fallen ill because she defied the Oba by trying to extort more money from a girl and no one can diagnose her illness.

“It is the effect of the curse placed by the Oba on those who cheat. That is the reason why she is sick,” she said.

For almost two decades, 42-year-old Patience earned a steady income sending girls from Nigeria to Europe for sex work, using black magic to stop the women from fleeing. Now, she is afraid the illegal trade could kill her.

During a ceremony in March, Oba Ewuare II, leader of the historic kingdom of Benin in southern Nigeria, invoked curses on anyone who used witchcraft to aid illegal migration.

Since then, anecdotal evidence suggests the trafficking has slowed although it is too soon for firm data to be collated.

The number of female Nigerians arriving in Italy by boat surged to more than 11,000 in 2016 from 1,500 in 2014, with at least four in five forced into prostitution, according to data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

At least nine in every 10 Nigerian women trafficked to Europe come from Edo, a mostly Christian state of 3 million people, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC).

Many came through the hands of women like Patience, who supplements her income as a hairdresser by selling girls into overseas sex work – but the leader’s ceremony has stopped that.

“I didn’t hear directly from his mouth but, through the radio and television. The Oba has stopped everything,” Patience told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in her home in Benin, where she lives with her husband and four children.

“Whenever I go out, I meet girls who beg me to take them to Europe but I refuse because I don’t want to die. Everybody is afraid.”

Belief in black magic is deep-rooted in Benin, and many fear crossing their traditional leader could incur death, mental breakdown or a myriad of unexplained physical ailments.

“You don’t know what exactly the penalty (of the curse) will be. The repercussions can come in several ways,” said David Edebiri, the second highest ranking chief in Benin.

He believes the Oba’s involvement, inspired by repeated bad press in the international media, has reduced trafficking and could help bring more traffickers to justice as many women involved were too afraid of juju rituals before to testify.

“It has been very, very effective and that if even anything is going on now, it must be a very minute dimension. Not as it was before (when) it was becoming everybody’s game,” he said.

Patience said she trafficked dozens of girls to Europe over the past 16 years, paid by Nigerian brokers in Europe or madams.

The madams told Patience when they needed more girls and she then set about recruiting, usually at her salon.

Before leaving, the girls signed a deal that locked them into repaying thousands of dollars of debt. Patience then took them to a spiritual priest to seal the pact with a ritual.

Known as juju, such black magic rituals instill fear in a girl that her relatives will fall ill or die if they disobey their traffickers, go to the police or fail to pay their debts.

“My face started rotting when I refused to pay any additional money. They took me to different hospitals and conducted all sorts of tests but no one could tell what was wrong with my face,” said Florence, 24, who was trafficked to Russia at the age of 18.

Florence said she paid at least $45,000 to her madam over five years of prostitution. Then she refused to pay more.

“It was the juju that affected me,” she said, stroking her face to describe the lesions that developed a week after she defied her trafficker’s demands for more money.

But when Oba Ewuare II banned juju priests from performing any ritual to aid the human trade, its effect was instant.

“No one will ever come here again,” said David Ubebe, a juju priest who for eight years attended to a flow of women bringing girls to swear oaths at his shrine as well as phone calls from madams in Europe asking him to compel girls to pay them.

He used to earn an undisclosed income for each black magic ritual he performed, boasting his powers could make someone menstruate nonstop or lose peace of mind, but is now too nervous to defy the ban.

The dingy shrine behind his home is now quieter, strewn with animal bones and carvings. Here girls were made to eat pieces of liver – yanked from live chickens – and bits of their hair and clothing were mixed into a concoction that he made them drink.

“No one disturbs me anymore,” he said. “Even if anybody requests that I use my powers to put pressure on the girls in Europe so that they will pay, I can’t do it, because I don’t want to die.”

Nduka Nwenwene, Edo zonal commander of Nigeria’s anti-trafficking agency (NAPTIP), said victims have become more willing to testify since the Oba revoked the juju curses.

“We are seeing the impact. People who hide out or refuse to come out to give evidence in court are now coming out,” said Nwanwene who has four anti-trafficking cases pending in court, including that of Florence who, with her mother, has boldly faced her traffickers in court.

Meanwhile Patience is convinced a madam she knows in Europe has fallen ill because she defied the Oba by trying to extort more money from a girl and no one can diagnose her illness.

“It is the effect of the curse placed by the Oba on those who cheat. That is the reason why she is sick,” she said.

For almost two decades, 42-year-old Patience earned a steady income sending girls from Nigeria to Europe for sex work, using black magic to stop the women from fleeing. Now, she is afraid the illegal trade could kill her.

During a ceremony in March, Oba Ewuare II, leader of the historic kingdom of Benin in southern Nigeria, invoked curses on anyone who used witchcraft to aid illegal migration.

Since then, anecdotal evidence suggests the trafficking has slowed although it is too soon for firm data to be collated.

The number of female Nigerians arriving in Italy by boat surged to more than 11,000 in 2016 from 1,500 in 2014, with at least four in five forced into prostitution, according to data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

At least nine in every 10 Nigerian women trafficked to Europe come from Edo, a mostly Christian state of 3 million people, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC).

Many came through the hands of women like Patience, who supplements her income as a hairdresser by selling girls into overseas sex work – but the leader’s ceremony has stopped that.

“I didn’t hear directly from his mouth but, through the radio and television. The Oba has stopped everything,” Patience told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in her home in Benin, where she lives with her husband and four children.

“Whenever I go out, I meet girls who beg me to take them to Europe but I refuse because I don’t want to die. Everybody is afraid.”

Belief in black magic is deep-rooted in Benin, and many fear crossing their traditional leader could incur death, mental breakdown or a myriad of unexplained physical ailments.

“You don’t know what exactly the penalty (of the curse) will be. The repercussions can come in several ways,” said David Edebiri, the second highest ranking chief in Benin.

He believes the Oba’s involvement, inspired by repeated bad press in the international media, has reduced trafficking and could help bring more traffickers to justice as many women involved were too afraid of juju rituals before to testify.

“It has been very, very effective and that if even anything is going on now, it must be a very minute dimension. Not as it was before (when) it was becoming everybody’s game,” he said.

Patience said she trafficked dozens of girls to Europe over the past 16 years, paid by Nigerian brokers in Europe or madams.

The madams told Patience when they needed more girls and she then set about recruiting, usually at her salon.

Before leaving, the girls signed a deal that locked them into repaying thousands of dollars of debt. Patience then took them to a spiritual priest to seal the pact with a ritual.

Known as juju, such black magic rituals instill fear in a girl that her relatives will fall ill or die if they disobey their traffickers, go to the police or fail to pay their debts.

“My face started rotting when I refused to pay any additional money. They took me to different hospitals and conducted all sorts of tests but no one could tell what was wrong with my face,” said Florence, 24, who was trafficked to Russia at the age of 18.

Florence said she paid at least $45,000 to her madam over five years of prostitution. Then she refused to pay more.

“It was the juju that affected me,” she said, stroking her face to describe the lesions that developed a week after she defied her trafficker’s demands for more money.

But when Oba Ewuare II banned juju priests from performing any ritual to aid the human trade, its effect was instant.

“No one will ever come here again,” said David Ubebe, a juju priest who for eight years attended to a flow of women bringing girls to swear oaths at his shrine as well as phone calls from madams in Europe asking him to compel girls to pay them.

He used to earn an undisclosed income for each black magic ritual he performed, boasting his powers could make someone menstruate nonstop or lose peace of mind, but is now too nervous to defy the ban.

The dingy shrine behind his home is now quieter, strewn with animal bones and carvings. Here girls were made to eat pieces of liver – yanked from live chickens – and bits of their hair and clothing were mixed into a concoction that he made them drink.

“No one disturbs me anymore,” he said. “Even if anybody requests that I use my powers to put pressure on the girls in Europe so that they will pay, I can’t do it, because I don’t want to die.”

Nduka Nwenwene, Edo zonal commander of Nigeria’s anti-trafficking agency (NAPTIP), said victims have become more willing to testify since the Oba revoked the juju curses.

“We are seeing the impact. People who hide out or refuse to come out to give evidence in court are now coming out,” said Nwanwene who has four anti-trafficking cases pending in court, including that of Florence who, with her mother, has boldly faced her traffickers in court.

Meanwhile Patience is convinced a madam she knows in Europe has fallen ill because she defied the Oba by trying to extort more money from a girl and no one can diagnose her illness.

“It is the effect of the curse placed by the Oba on those who cheat. That is the reason why she is sick,” she said.

For almost two decades, 42-year-old Patience earned a steady income sending girls from Nigeria to Europe for sex work, using black magic to stop the women from fleeing. Now, she is afraid the illegal trade could kill her.

During a ceremony in March, Oba Ewuare II, leader of the historic kingdom of Benin in southern Nigeria, invoked curses on anyone who used witchcraft to aid illegal migration.

Since then, anecdotal evidence suggests the trafficking has slowed although it is too soon for firm data to be collated.

The number of female Nigerians arriving in Italy by boat surged to more than 11,000 in 2016 from 1,500 in 2014, with at least four in five forced into prostitution, according to data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

At least nine in every 10 Nigerian women trafficked to Europe come from Edo, a mostly Christian state of 3 million people, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC).

Many came through the hands of women like Patience, who supplements her income as a hairdresser by selling girls into overseas sex work – but the leader’s ceremony has stopped that.

“I didn’t hear directly from his mouth but, through the radio and television. The Oba has stopped everything,” Patience told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in her home in Benin, where she lives with her husband and four children.

“Whenever I go out, I meet girls who beg me to take them to Europe but I refuse because I don’t want to die. Everybody is afraid.”

Belief in black magic is deep-rooted in Benin, and many fear crossing their traditional leader could incur death, mental breakdown or a myriad of unexplained physical ailments.

“You don’t know what exactly the penalty (of the curse) will be. The repercussions can come in several ways,” said David Edebiri, the second highest ranking chief in Benin.

He believes the Oba’s involvement, inspired by repeated bad press in the international media, has reduced trafficking and could help bring more traffickers to justice as many women involved were too afraid of juju rituals before to testify.

“It has been very, very effective and that if even anything is going on now, it must be a very minute dimension. Not as it was before (when) it was becoming everybody’s game,” he said.

Patience said she trafficked dozens of girls to Europe over the past 16 years, paid by Nigerian brokers in Europe or madams.

The madams told Patience when they needed more girls and she then set about recruiting, usually at her salon.

Before leaving, the girls signed a deal that locked them into repaying thousands of dollars of debt. Patience then took them to a spiritual priest to seal the pact with a ritual.

Known as juju, such black magic rituals instill fear in a girl that her relatives will fall ill or die if they disobey their traffickers, go to the police or fail to pay their debts.

“My face started rotting when I refused to pay any additional money. They took me to different hospitals and conducted all sorts of tests but no one could tell what was wrong with my face,” said Florence, 24, who was trafficked to Russia at the age of 18.

Florence said she paid at least $45,000 to her madam over five years of prostitution. Then she refused to pay more.

“It was the juju that affected me,” she said, stroking her face to describe the lesions that developed a week after she defied her trafficker’s demands for more money.

But when Oba Ewuare II banned juju priests from performing any ritual to aid the human trade, its effect was instant.

“No one will ever come here again,” said David Ubebe, a juju priest who for eight years attended to a flow of women bringing girls to swear oaths at his shrine as well as phone calls from madams in Europe asking him to compel girls to pay them.

He used to earn an undisclosed income for each black magic ritual he performed, boasting his powers could make someone menstruate nonstop or lose peace of mind, but is now too nervous to defy the ban.

The dingy shrine behind his home is now quieter, strewn with animal bones and carvings. Here girls were made to eat pieces of liver – yanked from live chickens – and bits of their hair and clothing were mixed into a concoction that he made them drink.

“No one disturbs me anymore,” he said. “Even if anybody requests that I use my powers to put pressure on the girls in Europe so that they will pay, I can’t do it, because I don’t want to die.”

Nduka Nwenwene, Edo zonal commander of Nigeria’s anti-trafficking agency (NAPTIP), said victims have become more willing to testify since the Oba revoked the juju curses.

“We are seeing the impact. People who hide out or refuse to come out to give evidence in court are now coming out,” said Nwanwene who has four anti-trafficking cases pending in court, including that of Florence who, with her mother, has boldly faced her traffickers in court.

Meanwhile Patience is convinced a madam she knows in Europe has fallen ill because she defied the Oba by trying to extort more money from a girl and no one can diagnose her illness.

“It is the effect of the curse placed by the Oba on those who cheat. That is the reason why she is sick,” she said.

For almost two decades, 42-year-old Patience earned a steady income sending girls from Nigeria to Europe for sex work, using black magic to stop the women from fleeing. Now, she is afraid the illegal trade could kill her.

During a ceremony in March, Oba Ewuare II, leader of the historic kingdom of Benin in southern Nigeria, invoked curses on anyone who used witchcraft to aid illegal migration.

Since then, anecdotal evidence suggests the trafficking has slowed although it is too soon for firm data to be collated.

The number of female Nigerians arriving in Italy by boat surged to more than 11,000 in 2016 from 1,500 in 2014, with at least four in five forced into prostitution, according to data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

At least nine in every 10 Nigerian women trafficked to Europe come from Edo, a mostly Christian state of 3 million people, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC).

Many came through the hands of women like Patience, who supplements her income as a hairdresser by selling girls into overseas sex work – but the leader’s ceremony has stopped that.

“I didn’t hear directly from his mouth but, through the radio and television. The Oba has stopped everything,” Patience told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in her home in Benin, where she lives with her husband and four children.

“Whenever I go out, I meet girls who beg me to take them to Europe but I refuse because I don’t want to die. Everybody is afraid.”

Belief in black magic is deep-rooted in Benin, and many fear crossing their traditional leader could incur death, mental breakdown or a myriad of unexplained physical ailments.

“You don’t know what exactly the penalty (of the curse) will be. The repercussions can come in several ways,” said David Edebiri, the second highest ranking chief in Benin.

He believes the Oba’s involvement, inspired by repeated bad press in the international media, has reduced trafficking and could help bring more traffickers to justice as many women involved were too afraid of juju rituals before to testify.

“It has been very, very effective and that if even anything is going on now, it must be a very minute dimension. Not as it was before (when) it was becoming everybody’s game,” he said.

Patience said she trafficked dozens of girls to Europe over the past 16 years, paid by Nigerian brokers in Europe or madams.

The madams told Patience when they needed more girls and she then set about recruiting, usually at her salon.

Before leaving, the girls signed a deal that locked them into repaying thousands of dollars of debt. Patience then took them to a spiritual priest to seal the pact with a ritual.

Known as juju, such black magic rituals instill fear in a girl that her relatives will fall ill or die if they disobey their traffickers, go to the police or fail to pay their debts.

“My face started rotting when I refused to pay any additional money. They took me to different hospitals and conducted all sorts of tests but no one could tell what was wrong with my face,” said Florence, 24, who was trafficked to Russia at the age of 18.

Florence said she paid at least $45,000 to her madam over five years of prostitution. Then she refused to pay more.

“It was the juju that affected me,” she said, stroking her face to describe the lesions that developed a week after she defied her trafficker’s demands for more money.

But when Oba Ewuare II banned juju priests from performing any ritual to aid the human trade, its effect was instant.

“No one will ever come here again,” said David Ubebe, a juju priest who for eight years attended to a flow of women bringing girls to swear oaths at his shrine as well as phone calls from madams in Europe asking him to compel girls to pay them.

He used to earn an undisclosed income for each black magic ritual he performed, boasting his powers could make someone menstruate nonstop or lose peace of mind, but is now too nervous to defy the ban.

The dingy shrine behind his home is now quieter, strewn with animal bones and carvings. Here girls were made to eat pieces of liver – yanked from live chickens – and bits of their hair and clothing were mixed into a concoction that he made them drink.

“No one disturbs me anymore,” he said. “Even if anybody requests that I use my powers to put pressure on the girls in Europe so that they will pay, I can’t do it, because I don’t want to die.”

Nduka Nwenwene, Edo zonal commander of Nigeria’s anti-trafficking agency (NAPTIP), said victims have become more willing to testify since the Oba revoked the juju curses.

“We are seeing the impact. People who hide out or refuse to come out to give evidence in court are now coming out,” said Nwanwene who has four anti-trafficking cases pending in court, including that of Florence who, with her mother, has boldly faced her traffickers in court.

Meanwhile Patience is convinced a madam she knows in Europe has fallen ill because she defied the Oba by trying to extort more money from a girl and no one can diagnose her illness.

“It is the effect of the curse placed by the Oba on those who cheat. That is the reason why she is sick,” she said.