The World Health Organisation has launched a strategy to rid the world of cervical cancer, stressing that broad use of vaccines, new tests and treatments could save five million lives by 2050.

“Eliminating any cancer would have once seemed an impossible dream, but we now have the cost-effective, evidence-based tools to make that dream a reality,” WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement.

More than half a million new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed around the world each year, hundreds of thousands of women die from the disease, and the WHO warns will rise significantly in the years to come without action.

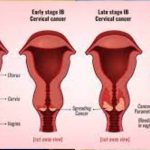

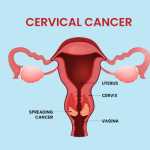

The good news is that cervical cancer, which is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) — a common sexually transmitted infection — is preventable with reliable and safe vaccines, and also curable if caught early and adequately treated.

During the WHO’s main annual meeting last week, all 194 member countries agreed to a plan towards eliminating the cancer.

“This is a huge milestone,” WHO Assistant Director-General Princess Nothemba Simelela told a virtual press briefing.

“For the first time the world has agreed to eliminate the only cancer we can prevent with a vaccine, and the only cancer which is curable if detected early,” she said.

The WHO forecasts that if countries do not act swiftly, the number of global cases could jump from 570,000 in 2018 to 700,000 by 2030, while deaths could increase from 311,000 to 400,000 during the same timeframe.

Simelela insisted “decades of neglect” were responsible for the high number of cervical cancer deaths, especially in low and middle-income countries, where there are twice as many cases and three times as many deaths from the disease as in wealthy nations.

While most high-income countries have introduced wide-spread vaccination, testing and treatment, access has remained far more difficult elsewhere, in part due to the high cost of vaccine doses.

“If we can improve access for low and middle-income countries we really can be on the road to elimination,” she said.

The strategy announced Tuesday calls on countries by 2030 to ensure that at least 90 per cent of girls to be fully vaccinated against HPV before they turn 15.

It also calls for at least 70 per cent of women to be tested for cervical cancer by the time they are 35 and again by 45, and for at least 90 per cent of women diagnosed with the disease to receive treatment.

While a range of recent advances promise to simplify testing, push down costs and ease access, WHO acknowledged that its new strategy comes at a challenging time, with the world focused on battling the Covid-19 pandemic.

The coronavirus crisis has interrupted vaccination, screening and treatment for cervical cancer, while border closures have reduced availability of supplies.

“We probably lost a sizable number of women,” Simelela said.

She added though that the testing infrastructure and systems being created for Covid-19 could hopefully be maintained for screening for other diseases, including cervical cancer.

“We can make history to ensure a cervical cancer-free future,” she said.

The World Health Organisation has launched a strategy to rid the world of cervical cancer, stressing that broad use of vaccines, new tests and treatments could save five million lives by 2050.

“Eliminating any cancer would have once seemed an impossible dream, but we now have the cost-effective, evidence-based tools to make that dream a reality,” WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement.

More than half a million new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed around the world each year, hundreds of thousands of women die from the disease, and the WHO warns will rise significantly in the years to come without action.

The good news is that cervical cancer, which is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) — a common sexually transmitted infection — is preventable with reliable and safe vaccines, and also curable if caught early and adequately treated.

During the WHO’s main annual meeting last week, all 194 member countries agreed to a plan towards eliminating the cancer.

“This is a huge milestone,” WHO Assistant Director-General Princess Nothemba Simelela told a virtual press briefing.

“For the first time the world has agreed to eliminate the only cancer we can prevent with a vaccine, and the only cancer which is curable if detected early,” she said.

The WHO forecasts that if countries do not act swiftly, the number of global cases could jump from 570,000 in 2018 to 700,000 by 2030, while deaths could increase from 311,000 to 400,000 during the same timeframe.

Simelela insisted “decades of neglect” were responsible for the high number of cervical cancer deaths, especially in low and middle-income countries, where there are twice as many cases and three times as many deaths from the disease as in wealthy nations.

While most high-income countries have introduced wide-spread vaccination, testing and treatment, access has remained far more difficult elsewhere, in part due to the high cost of vaccine doses.

“If we can improve access for low and middle-income countries we really can be on the road to elimination,” she said.

The strategy announced Tuesday calls on countries by 2030 to ensure that at least 90 per cent of girls to be fully vaccinated against HPV before they turn 15.

It also calls for at least 70 per cent of women to be tested for cervical cancer by the time they are 35 and again by 45, and for at least 90 per cent of women diagnosed with the disease to receive treatment.

While a range of recent advances promise to simplify testing, push down costs and ease access, WHO acknowledged that its new strategy comes at a challenging time, with the world focused on battling the Covid-19 pandemic.

The coronavirus crisis has interrupted vaccination, screening and treatment for cervical cancer, while border closures have reduced availability of supplies.

“We probably lost a sizable number of women,” Simelela said.

She added though that the testing infrastructure and systems being created for Covid-19 could hopefully be maintained for screening for other diseases, including cervical cancer.

“We can make history to ensure a cervical cancer-free future,” she said.

The World Health Organisation has launched a strategy to rid the world of cervical cancer, stressing that broad use of vaccines, new tests and treatments could save five million lives by 2050.

“Eliminating any cancer would have once seemed an impossible dream, but we now have the cost-effective, evidence-based tools to make that dream a reality,” WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement.

More than half a million new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed around the world each year, hundreds of thousands of women die from the disease, and the WHO warns will rise significantly in the years to come without action.

The good news is that cervical cancer, which is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) — a common sexually transmitted infection — is preventable with reliable and safe vaccines, and also curable if caught early and adequately treated.

During the WHO’s main annual meeting last week, all 194 member countries agreed to a plan towards eliminating the cancer.

“This is a huge milestone,” WHO Assistant Director-General Princess Nothemba Simelela told a virtual press briefing.

“For the first time the world has agreed to eliminate the only cancer we can prevent with a vaccine, and the only cancer which is curable if detected early,” she said.

The WHO forecasts that if countries do not act swiftly, the number of global cases could jump from 570,000 in 2018 to 700,000 by 2030, while deaths could increase from 311,000 to 400,000 during the same timeframe.

Simelela insisted “decades of neglect” were responsible for the high number of cervical cancer deaths, especially in low and middle-income countries, where there are twice as many cases and three times as many deaths from the disease as in wealthy nations.

While most high-income countries have introduced wide-spread vaccination, testing and treatment, access has remained far more difficult elsewhere, in part due to the high cost of vaccine doses.

“If we can improve access for low and middle-income countries we really can be on the road to elimination,” she said.

The strategy announced Tuesday calls on countries by 2030 to ensure that at least 90 per cent of girls to be fully vaccinated against HPV before they turn 15.

It also calls for at least 70 per cent of women to be tested for cervical cancer by the time they are 35 and again by 45, and for at least 90 per cent of women diagnosed with the disease to receive treatment.

While a range of recent advances promise to simplify testing, push down costs and ease access, WHO acknowledged that its new strategy comes at a challenging time, with the world focused on battling the Covid-19 pandemic.

The coronavirus crisis has interrupted vaccination, screening and treatment for cervical cancer, while border closures have reduced availability of supplies.

“We probably lost a sizable number of women,” Simelela said.

She added though that the testing infrastructure and systems being created for Covid-19 could hopefully be maintained for screening for other diseases, including cervical cancer.

“We can make history to ensure a cervical cancer-free future,” she said.

The World Health Organisation has launched a strategy to rid the world of cervical cancer, stressing that broad use of vaccines, new tests and treatments could save five million lives by 2050.

“Eliminating any cancer would have once seemed an impossible dream, but we now have the cost-effective, evidence-based tools to make that dream a reality,” WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement.

More than half a million new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed around the world each year, hundreds of thousands of women die from the disease, and the WHO warns will rise significantly in the years to come without action.

The good news is that cervical cancer, which is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) — a common sexually transmitted infection — is preventable with reliable and safe vaccines, and also curable if caught early and adequately treated.

During the WHO’s main annual meeting last week, all 194 member countries agreed to a plan towards eliminating the cancer.

“This is a huge milestone,” WHO Assistant Director-General Princess Nothemba Simelela told a virtual press briefing.

“For the first time the world has agreed to eliminate the only cancer we can prevent with a vaccine, and the only cancer which is curable if detected early,” she said.

The WHO forecasts that if countries do not act swiftly, the number of global cases could jump from 570,000 in 2018 to 700,000 by 2030, while deaths could increase from 311,000 to 400,000 during the same timeframe.

Simelela insisted “decades of neglect” were responsible for the high number of cervical cancer deaths, especially in low and middle-income countries, where there are twice as many cases and three times as many deaths from the disease as in wealthy nations.

While most high-income countries have introduced wide-spread vaccination, testing and treatment, access has remained far more difficult elsewhere, in part due to the high cost of vaccine doses.

“If we can improve access for low and middle-income countries we really can be on the road to elimination,” she said.

The strategy announced Tuesday calls on countries by 2030 to ensure that at least 90 per cent of girls to be fully vaccinated against HPV before they turn 15.

It also calls for at least 70 per cent of women to be tested for cervical cancer by the time they are 35 and again by 45, and for at least 90 per cent of women diagnosed with the disease to receive treatment.

While a range of recent advances promise to simplify testing, push down costs and ease access, WHO acknowledged that its new strategy comes at a challenging time, with the world focused on battling the Covid-19 pandemic.

The coronavirus crisis has interrupted vaccination, screening and treatment for cervical cancer, while border closures have reduced availability of supplies.

“We probably lost a sizable number of women,” Simelela said.

She added though that the testing infrastructure and systems being created for Covid-19 could hopefully be maintained for screening for other diseases, including cervical cancer.

“We can make history to ensure a cervical cancer-free future,” she said.

The World Health Organisation has launched a strategy to rid the world of cervical cancer, stressing that broad use of vaccines, new tests and treatments could save five million lives by 2050.

“Eliminating any cancer would have once seemed an impossible dream, but we now have the cost-effective, evidence-based tools to make that dream a reality,” WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement.

More than half a million new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed around the world each year, hundreds of thousands of women die from the disease, and the WHO warns will rise significantly in the years to come without action.

The good news is that cervical cancer, which is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) — a common sexually transmitted infection — is preventable with reliable and safe vaccines, and also curable if caught early and adequately treated.

During the WHO’s main annual meeting last week, all 194 member countries agreed to a plan towards eliminating the cancer.

“This is a huge milestone,” WHO Assistant Director-General Princess Nothemba Simelela told a virtual press briefing.

“For the first time the world has agreed to eliminate the only cancer we can prevent with a vaccine, and the only cancer which is curable if detected early,” she said.

The WHO forecasts that if countries do not act swiftly, the number of global cases could jump from 570,000 in 2018 to 700,000 by 2030, while deaths could increase from 311,000 to 400,000 during the same timeframe.

Simelela insisted “decades of neglect” were responsible for the high number of cervical cancer deaths, especially in low and middle-income countries, where there are twice as many cases and three times as many deaths from the disease as in wealthy nations.

While most high-income countries have introduced wide-spread vaccination, testing and treatment, access has remained far more difficult elsewhere, in part due to the high cost of vaccine doses.

“If we can improve access for low and middle-income countries we really can be on the road to elimination,” she said.

The strategy announced Tuesday calls on countries by 2030 to ensure that at least 90 per cent of girls to be fully vaccinated against HPV before they turn 15.

It also calls for at least 70 per cent of women to be tested for cervical cancer by the time they are 35 and again by 45, and for at least 90 per cent of women diagnosed with the disease to receive treatment.

While a range of recent advances promise to simplify testing, push down costs and ease access, WHO acknowledged that its new strategy comes at a challenging time, with the world focused on battling the Covid-19 pandemic.

The coronavirus crisis has interrupted vaccination, screening and treatment for cervical cancer, while border closures have reduced availability of supplies.

“We probably lost a sizable number of women,” Simelela said.

She added though that the testing infrastructure and systems being created for Covid-19 could hopefully be maintained for screening for other diseases, including cervical cancer.

“We can make history to ensure a cervical cancer-free future,” she said.

The World Health Organisation has launched a strategy to rid the world of cervical cancer, stressing that broad use of vaccines, new tests and treatments could save five million lives by 2050.

“Eliminating any cancer would have once seemed an impossible dream, but we now have the cost-effective, evidence-based tools to make that dream a reality,” WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement.

More than half a million new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed around the world each year, hundreds of thousands of women die from the disease, and the WHO warns will rise significantly in the years to come without action.

The good news is that cervical cancer, which is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) — a common sexually transmitted infection — is preventable with reliable and safe vaccines, and also curable if caught early and adequately treated.

During the WHO’s main annual meeting last week, all 194 member countries agreed to a plan towards eliminating the cancer.

“This is a huge milestone,” WHO Assistant Director-General Princess Nothemba Simelela told a virtual press briefing.

“For the first time the world has agreed to eliminate the only cancer we can prevent with a vaccine, and the only cancer which is curable if detected early,” she said.

The WHO forecasts that if countries do not act swiftly, the number of global cases could jump from 570,000 in 2018 to 700,000 by 2030, while deaths could increase from 311,000 to 400,000 during the same timeframe.

Simelela insisted “decades of neglect” were responsible for the high number of cervical cancer deaths, especially in low and middle-income countries, where there are twice as many cases and three times as many deaths from the disease as in wealthy nations.

While most high-income countries have introduced wide-spread vaccination, testing and treatment, access has remained far more difficult elsewhere, in part due to the high cost of vaccine doses.

“If we can improve access for low and middle-income countries we really can be on the road to elimination,” she said.

The strategy announced Tuesday calls on countries by 2030 to ensure that at least 90 per cent of girls to be fully vaccinated against HPV before they turn 15.

It also calls for at least 70 per cent of women to be tested for cervical cancer by the time they are 35 and again by 45, and for at least 90 per cent of women diagnosed with the disease to receive treatment.

While a range of recent advances promise to simplify testing, push down costs and ease access, WHO acknowledged that its new strategy comes at a challenging time, with the world focused on battling the Covid-19 pandemic.

The coronavirus crisis has interrupted vaccination, screening and treatment for cervical cancer, while border closures have reduced availability of supplies.

“We probably lost a sizable number of women,” Simelela said.

She added though that the testing infrastructure and systems being created for Covid-19 could hopefully be maintained for screening for other diseases, including cervical cancer.

“We can make history to ensure a cervical cancer-free future,” she said.

The World Health Organisation has launched a strategy to rid the world of cervical cancer, stressing that broad use of vaccines, new tests and treatments could save five million lives by 2050.

“Eliminating any cancer would have once seemed an impossible dream, but we now have the cost-effective, evidence-based tools to make that dream a reality,” WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement.

More than half a million new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed around the world each year, hundreds of thousands of women die from the disease, and the WHO warns will rise significantly in the years to come without action.

The good news is that cervical cancer, which is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) — a common sexually transmitted infection — is preventable with reliable and safe vaccines, and also curable if caught early and adequately treated.

During the WHO’s main annual meeting last week, all 194 member countries agreed to a plan towards eliminating the cancer.

“This is a huge milestone,” WHO Assistant Director-General Princess Nothemba Simelela told a virtual press briefing.

“For the first time the world has agreed to eliminate the only cancer we can prevent with a vaccine, and the only cancer which is curable if detected early,” she said.

The WHO forecasts that if countries do not act swiftly, the number of global cases could jump from 570,000 in 2018 to 700,000 by 2030, while deaths could increase from 311,000 to 400,000 during the same timeframe.

Simelela insisted “decades of neglect” were responsible for the high number of cervical cancer deaths, especially in low and middle-income countries, where there are twice as many cases and three times as many deaths from the disease as in wealthy nations.

While most high-income countries have introduced wide-spread vaccination, testing and treatment, access has remained far more difficult elsewhere, in part due to the high cost of vaccine doses.

“If we can improve access for low and middle-income countries we really can be on the road to elimination,” she said.

The strategy announced Tuesday calls on countries by 2030 to ensure that at least 90 per cent of girls to be fully vaccinated against HPV before they turn 15.

It also calls for at least 70 per cent of women to be tested for cervical cancer by the time they are 35 and again by 45, and for at least 90 per cent of women diagnosed with the disease to receive treatment.

While a range of recent advances promise to simplify testing, push down costs and ease access, WHO acknowledged that its new strategy comes at a challenging time, with the world focused on battling the Covid-19 pandemic.

The coronavirus crisis has interrupted vaccination, screening and treatment for cervical cancer, while border closures have reduced availability of supplies.

“We probably lost a sizable number of women,” Simelela said.

She added though that the testing infrastructure and systems being created for Covid-19 could hopefully be maintained for screening for other diseases, including cervical cancer.

“We can make history to ensure a cervical cancer-free future,” she said.

The World Health Organisation has launched a strategy to rid the world of cervical cancer, stressing that broad use of vaccines, new tests and treatments could save five million lives by 2050.

“Eliminating any cancer would have once seemed an impossible dream, but we now have the cost-effective, evidence-based tools to make that dream a reality,” WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement.

More than half a million new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed around the world each year, hundreds of thousands of women die from the disease, and the WHO warns will rise significantly in the years to come without action.

The good news is that cervical cancer, which is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV) — a common sexually transmitted infection — is preventable with reliable and safe vaccines, and also curable if caught early and adequately treated.

During the WHO’s main annual meeting last week, all 194 member countries agreed to a plan towards eliminating the cancer.

“This is a huge milestone,” WHO Assistant Director-General Princess Nothemba Simelela told a virtual press briefing.

“For the first time the world has agreed to eliminate the only cancer we can prevent with a vaccine, and the only cancer which is curable if detected early,” she said.

The WHO forecasts that if countries do not act swiftly, the number of global cases could jump from 570,000 in 2018 to 700,000 by 2030, while deaths could increase from 311,000 to 400,000 during the same timeframe.

Simelela insisted “decades of neglect” were responsible for the high number of cervical cancer deaths, especially in low and middle-income countries, where there are twice as many cases and three times as many deaths from the disease as in wealthy nations.

While most high-income countries have introduced wide-spread vaccination, testing and treatment, access has remained far more difficult elsewhere, in part due to the high cost of vaccine doses.

“If we can improve access for low and middle-income countries we really can be on the road to elimination,” she said.

The strategy announced Tuesday calls on countries by 2030 to ensure that at least 90 per cent of girls to be fully vaccinated against HPV before they turn 15.

It also calls for at least 70 per cent of women to be tested for cervical cancer by the time they are 35 and again by 45, and for at least 90 per cent of women diagnosed with the disease to receive treatment.

While a range of recent advances promise to simplify testing, push down costs and ease access, WHO acknowledged that its new strategy comes at a challenging time, with the world focused on battling the Covid-19 pandemic.

The coronavirus crisis has interrupted vaccination, screening and treatment for cervical cancer, while border closures have reduced availability of supplies.

“We probably lost a sizable number of women,” Simelela said.

She added though that the testing infrastructure and systems being created for Covid-19 could hopefully be maintained for screening for other diseases, including cervical cancer.

“We can make history to ensure a cervical cancer-free future,” she said.