Some patients with a common nighttime breathing disorder known as obstructive sleep apnea may do just as well at managing the condition when they see a primary care provider instead of a specialist, a research review suggests.

“We found that in general, outcomes such as sleepiness, quality of life, and treatment adherence were similar,” said senior study author Dr. Timothy Wilt of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System and the University of Minnesota School of Medicine.

“Patients with daytime sleepiness could be adequately evaluated and treated by primary care providers who have additional sleep training, especially if access to sleep specialists is limited and if there is unmet demand for sleep apnea services,” Wilt said by email. “However, there is not yet sufficient evidence to support widespread migration of sleep apnea care away from sleep physicians.”

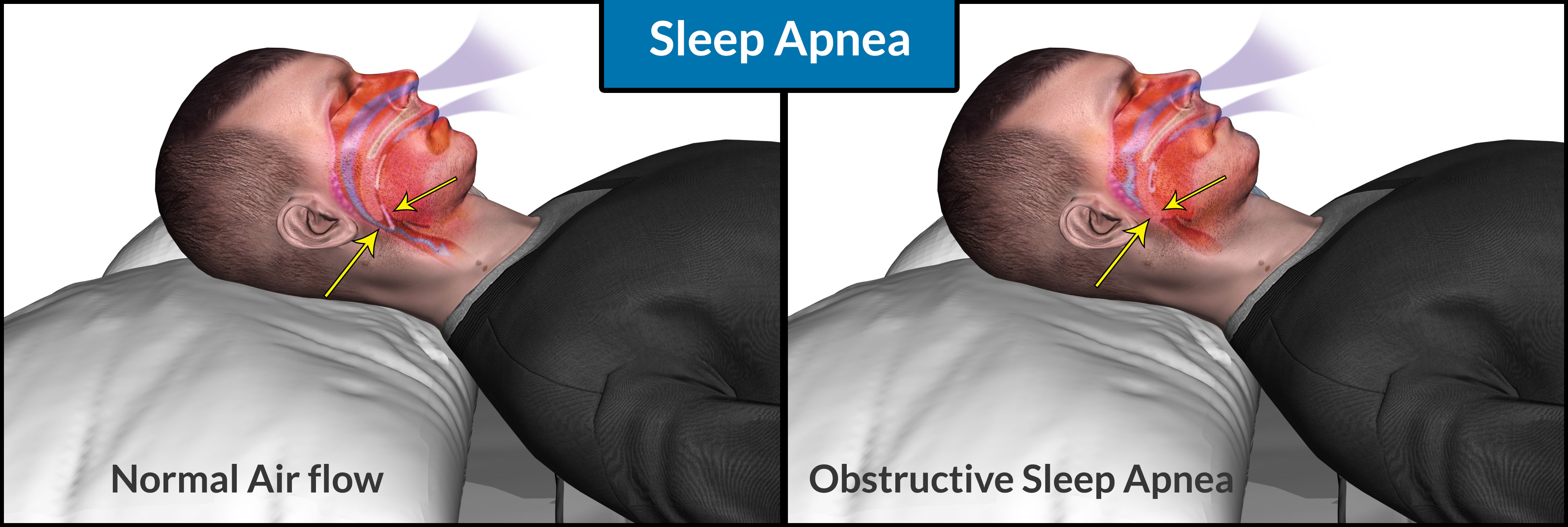

Millions of patients worldwide wear breathing masks all night to ease sleep apnea, a common disorder that leads to disrupted breathing or shallow breaths during sleep. The masks are connected to a machine that provides continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which splints the airway open with an airstream so the upper airway can’t collapse during sleep.

Some patients who can’t tolerate wearing the breathing masks all night may use an alternative apnea treatment known as mandibular advancement devices, which open up space in the airway by pushing out the lower jaw bone to make it less likely that the upper airway collapses during sleep.

Apnea that isn’t properly treated has been linked with excessive daytime sleepiness, decreased quality of life, heart attacks and heart failure, researchers note in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The current study set out to determine if primary care providers who received additional training in diagnosing and treating sleep disorders could manage apnea patients as well as specialists.

Apnea patients cared for by primary care providers had similar outcomes for symptom relief, adherence to prescribed treatments and quality of life as apnea patients seen by specialists, an analysis of 8 previously published studies with a total of 1,515 patients found.

Specialists and primary care providers also appeared to agree on the diagnosis and severity of apnea, an analysis of four smaller studies with a total of 580 patients found.

Researchers rated the quality of the evidence as low, however, and concluded that more studies are still needed to confirm whether some apnea patients could be treated without seeing specialists.

Another limitation of the study is that even the primary care providers still had extensive training in sleep medicine, making it unclear if all apnea patients would get similar outcomes from their own primary care provider, who might not have this training.

“Also, the studies reviewed were mostly done in obese, middle-aged males with moderate-to-severe apnea,” said Marie-Pierre St-Onge, a researcher at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City who wasn’t involved in the study.

“It is not known if similar results would be seen in patients with more complex cases or low probability for sleep apnea, women, elderly, or those with (other chronic health problems) which are quite prevalent in patients with sleep apnea,” St-Onge said by email.

Still, the results do suggest that it may be possible to get an accurate diagnosis of sleep apnea in primary care, noted Kristen Knutson, a researcher at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago who wasn’t involved in the study.

“If a patient is prescribed treatment for obstructive sleep apnea by a non-specialist and it seems to be working for them, then they probably don’t need to see a specialist,” Knutson said by email. “However, if the treatment does not seem to work well, it is uncomfortable, or they are still sleepy, then that patient could consider a specialist who would have more experience with different treatment options.”

Some patients with a common nighttime breathing disorder known as obstructive sleep apnea may do just as well at managing the condition when they see a primary care provider instead of a specialist, a research review suggests.

“We found that in general, outcomes such as sleepiness, quality of life, and treatment adherence were similar,” said senior study author Dr. Timothy Wilt of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System and the University of Minnesota School of Medicine.

“Patients with daytime sleepiness could be adequately evaluated and treated by primary care providers who have additional sleep training, especially if access to sleep specialists is limited and if there is unmet demand for sleep apnea services,” Wilt said by email. “However, there is not yet sufficient evidence to support widespread migration of sleep apnea care away from sleep physicians.”

Millions of patients worldwide wear breathing masks all night to ease sleep apnea, a common disorder that leads to disrupted breathing or shallow breaths during sleep. The masks are connected to a machine that provides continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which splints the airway open with an airstream so the upper airway can’t collapse during sleep.

Some patients who can’t tolerate wearing the breathing masks all night may use an alternative apnea treatment known as mandibular advancement devices, which open up space in the airway by pushing out the lower jaw bone to make it less likely that the upper airway collapses during sleep.

Apnea that isn’t properly treated has been linked with excessive daytime sleepiness, decreased quality of life, heart attacks and heart failure, researchers note in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The current study set out to determine if primary care providers who received additional training in diagnosing and treating sleep disorders could manage apnea patients as well as specialists.

Apnea patients cared for by primary care providers had similar outcomes for symptom relief, adherence to prescribed treatments and quality of life as apnea patients seen by specialists, an analysis of 8 previously published studies with a total of 1,515 patients found.

Specialists and primary care providers also appeared to agree on the diagnosis and severity of apnea, an analysis of four smaller studies with a total of 580 patients found.

Researchers rated the quality of the evidence as low, however, and concluded that more studies are still needed to confirm whether some apnea patients could be treated without seeing specialists.

Another limitation of the study is that even the primary care providers still had extensive training in sleep medicine, making it unclear if all apnea patients would get similar outcomes from their own primary care provider, who might not have this training.

“Also, the studies reviewed were mostly done in obese, middle-aged males with moderate-to-severe apnea,” said Marie-Pierre St-Onge, a researcher at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City who wasn’t involved in the study.

“It is not known if similar results would be seen in patients with more complex cases or low probability for sleep apnea, women, elderly, or those with (other chronic health problems) which are quite prevalent in patients with sleep apnea,” St-Onge said by email.

Still, the results do suggest that it may be possible to get an accurate diagnosis of sleep apnea in primary care, noted Kristen Knutson, a researcher at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago who wasn’t involved in the study.

“If a patient is prescribed treatment for obstructive sleep apnea by a non-specialist and it seems to be working for them, then they probably don’t need to see a specialist,” Knutson said by email. “However, if the treatment does not seem to work well, it is uncomfortable, or they are still sleepy, then that patient could consider a specialist who would have more experience with different treatment options.”

Some patients with a common nighttime breathing disorder known as obstructive sleep apnea may do just as well at managing the condition when they see a primary care provider instead of a specialist, a research review suggests.

“We found that in general, outcomes such as sleepiness, quality of life, and treatment adherence were similar,” said senior study author Dr. Timothy Wilt of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System and the University of Minnesota School of Medicine.

“Patients with daytime sleepiness could be adequately evaluated and treated by primary care providers who have additional sleep training, especially if access to sleep specialists is limited and if there is unmet demand for sleep apnea services,” Wilt said by email. “However, there is not yet sufficient evidence to support widespread migration of sleep apnea care away from sleep physicians.”

Millions of patients worldwide wear breathing masks all night to ease sleep apnea, a common disorder that leads to disrupted breathing or shallow breaths during sleep. The masks are connected to a machine that provides continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which splints the airway open with an airstream so the upper airway can’t collapse during sleep.

Some patients who can’t tolerate wearing the breathing masks all night may use an alternative apnea treatment known as mandibular advancement devices, which open up space in the airway by pushing out the lower jaw bone to make it less likely that the upper airway collapses during sleep.

Apnea that isn’t properly treated has been linked with excessive daytime sleepiness, decreased quality of life, heart attacks and heart failure, researchers note in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The current study set out to determine if primary care providers who received additional training in diagnosing and treating sleep disorders could manage apnea patients as well as specialists.

Apnea patients cared for by primary care providers had similar outcomes for symptom relief, adherence to prescribed treatments and quality of life as apnea patients seen by specialists, an analysis of 8 previously published studies with a total of 1,515 patients found.

Specialists and primary care providers also appeared to agree on the diagnosis and severity of apnea, an analysis of four smaller studies with a total of 580 patients found.

Researchers rated the quality of the evidence as low, however, and concluded that more studies are still needed to confirm whether some apnea patients could be treated without seeing specialists.

Another limitation of the study is that even the primary care providers still had extensive training in sleep medicine, making it unclear if all apnea patients would get similar outcomes from their own primary care provider, who might not have this training.

“Also, the studies reviewed were mostly done in obese, middle-aged males with moderate-to-severe apnea,” said Marie-Pierre St-Onge, a researcher at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City who wasn’t involved in the study.

“It is not known if similar results would be seen in patients with more complex cases or low probability for sleep apnea, women, elderly, or those with (other chronic health problems) which are quite prevalent in patients with sleep apnea,” St-Onge said by email.

Still, the results do suggest that it may be possible to get an accurate diagnosis of sleep apnea in primary care, noted Kristen Knutson, a researcher at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago who wasn’t involved in the study.

“If a patient is prescribed treatment for obstructive sleep apnea by a non-specialist and it seems to be working for them, then they probably don’t need to see a specialist,” Knutson said by email. “However, if the treatment does not seem to work well, it is uncomfortable, or they are still sleepy, then that patient could consider a specialist who would have more experience with different treatment options.”

Some patients with a common nighttime breathing disorder known as obstructive sleep apnea may do just as well at managing the condition when they see a primary care provider instead of a specialist, a research review suggests.

“We found that in general, outcomes such as sleepiness, quality of life, and treatment adherence were similar,” said senior study author Dr. Timothy Wilt of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System and the University of Minnesota School of Medicine.

“Patients with daytime sleepiness could be adequately evaluated and treated by primary care providers who have additional sleep training, especially if access to sleep specialists is limited and if there is unmet demand for sleep apnea services,” Wilt said by email. “However, there is not yet sufficient evidence to support widespread migration of sleep apnea care away from sleep physicians.”

Millions of patients worldwide wear breathing masks all night to ease sleep apnea, a common disorder that leads to disrupted breathing or shallow breaths during sleep. The masks are connected to a machine that provides continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which splints the airway open with an airstream so the upper airway can’t collapse during sleep.

Some patients who can’t tolerate wearing the breathing masks all night may use an alternative apnea treatment known as mandibular advancement devices, which open up space in the airway by pushing out the lower jaw bone to make it less likely that the upper airway collapses during sleep.

Apnea that isn’t properly treated has been linked with excessive daytime sleepiness, decreased quality of life, heart attacks and heart failure, researchers note in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The current study set out to determine if primary care providers who received additional training in diagnosing and treating sleep disorders could manage apnea patients as well as specialists.

Apnea patients cared for by primary care providers had similar outcomes for symptom relief, adherence to prescribed treatments and quality of life as apnea patients seen by specialists, an analysis of 8 previously published studies with a total of 1,515 patients found.

Specialists and primary care providers also appeared to agree on the diagnosis and severity of apnea, an analysis of four smaller studies with a total of 580 patients found.

Researchers rated the quality of the evidence as low, however, and concluded that more studies are still needed to confirm whether some apnea patients could be treated without seeing specialists.

Another limitation of the study is that even the primary care providers still had extensive training in sleep medicine, making it unclear if all apnea patients would get similar outcomes from their own primary care provider, who might not have this training.

“Also, the studies reviewed were mostly done in obese, middle-aged males with moderate-to-severe apnea,” said Marie-Pierre St-Onge, a researcher at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City who wasn’t involved in the study.

“It is not known if similar results would be seen in patients with more complex cases or low probability for sleep apnea, women, elderly, or those with (other chronic health problems) which are quite prevalent in patients with sleep apnea,” St-Onge said by email.

Still, the results do suggest that it may be possible to get an accurate diagnosis of sleep apnea in primary care, noted Kristen Knutson, a researcher at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago who wasn’t involved in the study.

“If a patient is prescribed treatment for obstructive sleep apnea by a non-specialist and it seems to be working for them, then they probably don’t need to see a specialist,” Knutson said by email. “However, if the treatment does not seem to work well, it is uncomfortable, or they are still sleepy, then that patient could consider a specialist who would have more experience with different treatment options.”

Some patients with a common nighttime breathing disorder known as obstructive sleep apnea may do just as well at managing the condition when they see a primary care provider instead of a specialist, a research review suggests.

“We found that in general, outcomes such as sleepiness, quality of life, and treatment adherence were similar,” said senior study author Dr. Timothy Wilt of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System and the University of Minnesota School of Medicine.

“Patients with daytime sleepiness could be adequately evaluated and treated by primary care providers who have additional sleep training, especially if access to sleep specialists is limited and if there is unmet demand for sleep apnea services,” Wilt said by email. “However, there is not yet sufficient evidence to support widespread migration of sleep apnea care away from sleep physicians.”

Millions of patients worldwide wear breathing masks all night to ease sleep apnea, a common disorder that leads to disrupted breathing or shallow breaths during sleep. The masks are connected to a machine that provides continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which splints the airway open with an airstream so the upper airway can’t collapse during sleep.

Some patients who can’t tolerate wearing the breathing masks all night may use an alternative apnea treatment known as mandibular advancement devices, which open up space in the airway by pushing out the lower jaw bone to make it less likely that the upper airway collapses during sleep.

Apnea that isn’t properly treated has been linked with excessive daytime sleepiness, decreased quality of life, heart attacks and heart failure, researchers note in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The current study set out to determine if primary care providers who received additional training in diagnosing and treating sleep disorders could manage apnea patients as well as specialists.

Apnea patients cared for by primary care providers had similar outcomes for symptom relief, adherence to prescribed treatments and quality of life as apnea patients seen by specialists, an analysis of 8 previously published studies with a total of 1,515 patients found.

Specialists and primary care providers also appeared to agree on the diagnosis and severity of apnea, an analysis of four smaller studies with a total of 580 patients found.

Researchers rated the quality of the evidence as low, however, and concluded that more studies are still needed to confirm whether some apnea patients could be treated without seeing specialists.

Another limitation of the study is that even the primary care providers still had extensive training in sleep medicine, making it unclear if all apnea patients would get similar outcomes from their own primary care provider, who might not have this training.

“Also, the studies reviewed were mostly done in obese, middle-aged males with moderate-to-severe apnea,” said Marie-Pierre St-Onge, a researcher at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City who wasn’t involved in the study.

“It is not known if similar results would be seen in patients with more complex cases or low probability for sleep apnea, women, elderly, or those with (other chronic health problems) which are quite prevalent in patients with sleep apnea,” St-Onge said by email.

Still, the results do suggest that it may be possible to get an accurate diagnosis of sleep apnea in primary care, noted Kristen Knutson, a researcher at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago who wasn’t involved in the study.

“If a patient is prescribed treatment for obstructive sleep apnea by a non-specialist and it seems to be working for them, then they probably don’t need to see a specialist,” Knutson said by email. “However, if the treatment does not seem to work well, it is uncomfortable, or they are still sleepy, then that patient could consider a specialist who would have more experience with different treatment options.”

Some patients with a common nighttime breathing disorder known as obstructive sleep apnea may do just as well at managing the condition when they see a primary care provider instead of a specialist, a research review suggests.

“We found that in general, outcomes such as sleepiness, quality of life, and treatment adherence were similar,” said senior study author Dr. Timothy Wilt of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System and the University of Minnesota School of Medicine.

“Patients with daytime sleepiness could be adequately evaluated and treated by primary care providers who have additional sleep training, especially if access to sleep specialists is limited and if there is unmet demand for sleep apnea services,” Wilt said by email. “However, there is not yet sufficient evidence to support widespread migration of sleep apnea care away from sleep physicians.”

Millions of patients worldwide wear breathing masks all night to ease sleep apnea, a common disorder that leads to disrupted breathing or shallow breaths during sleep. The masks are connected to a machine that provides continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which splints the airway open with an airstream so the upper airway can’t collapse during sleep.

Some patients who can’t tolerate wearing the breathing masks all night may use an alternative apnea treatment known as mandibular advancement devices, which open up space in the airway by pushing out the lower jaw bone to make it less likely that the upper airway collapses during sleep.

Apnea that isn’t properly treated has been linked with excessive daytime sleepiness, decreased quality of life, heart attacks and heart failure, researchers note in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The current study set out to determine if primary care providers who received additional training in diagnosing and treating sleep disorders could manage apnea patients as well as specialists.

Apnea patients cared for by primary care providers had similar outcomes for symptom relief, adherence to prescribed treatments and quality of life as apnea patients seen by specialists, an analysis of 8 previously published studies with a total of 1,515 patients found.

Specialists and primary care providers also appeared to agree on the diagnosis and severity of apnea, an analysis of four smaller studies with a total of 580 patients found.

Researchers rated the quality of the evidence as low, however, and concluded that more studies are still needed to confirm whether some apnea patients could be treated without seeing specialists.

Another limitation of the study is that even the primary care providers still had extensive training in sleep medicine, making it unclear if all apnea patients would get similar outcomes from their own primary care provider, who might not have this training.

“Also, the studies reviewed were mostly done in obese, middle-aged males with moderate-to-severe apnea,” said Marie-Pierre St-Onge, a researcher at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City who wasn’t involved in the study.

“It is not known if similar results would be seen in patients with more complex cases or low probability for sleep apnea, women, elderly, or those with (other chronic health problems) which are quite prevalent in patients with sleep apnea,” St-Onge said by email.

Still, the results do suggest that it may be possible to get an accurate diagnosis of sleep apnea in primary care, noted Kristen Knutson, a researcher at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago who wasn’t involved in the study.

“If a patient is prescribed treatment for obstructive sleep apnea by a non-specialist and it seems to be working for them, then they probably don’t need to see a specialist,” Knutson said by email. “However, if the treatment does not seem to work well, it is uncomfortable, or they are still sleepy, then that patient could consider a specialist who would have more experience with different treatment options.”

Some patients with a common nighttime breathing disorder known as obstructive sleep apnea may do just as well at managing the condition when they see a primary care provider instead of a specialist, a research review suggests.

“We found that in general, outcomes such as sleepiness, quality of life, and treatment adherence were similar,” said senior study author Dr. Timothy Wilt of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System and the University of Minnesota School of Medicine.

“Patients with daytime sleepiness could be adequately evaluated and treated by primary care providers who have additional sleep training, especially if access to sleep specialists is limited and if there is unmet demand for sleep apnea services,” Wilt said by email. “However, there is not yet sufficient evidence to support widespread migration of sleep apnea care away from sleep physicians.”

Millions of patients worldwide wear breathing masks all night to ease sleep apnea, a common disorder that leads to disrupted breathing or shallow breaths during sleep. The masks are connected to a machine that provides continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which splints the airway open with an airstream so the upper airway can’t collapse during sleep.

Some patients who can’t tolerate wearing the breathing masks all night may use an alternative apnea treatment known as mandibular advancement devices, which open up space in the airway by pushing out the lower jaw bone to make it less likely that the upper airway collapses during sleep.

Apnea that isn’t properly treated has been linked with excessive daytime sleepiness, decreased quality of life, heart attacks and heart failure, researchers note in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The current study set out to determine if primary care providers who received additional training in diagnosing and treating sleep disorders could manage apnea patients as well as specialists.

Apnea patients cared for by primary care providers had similar outcomes for symptom relief, adherence to prescribed treatments and quality of life as apnea patients seen by specialists, an analysis of 8 previously published studies with a total of 1,515 patients found.

Specialists and primary care providers also appeared to agree on the diagnosis and severity of apnea, an analysis of four smaller studies with a total of 580 patients found.

Researchers rated the quality of the evidence as low, however, and concluded that more studies are still needed to confirm whether some apnea patients could be treated without seeing specialists.

Another limitation of the study is that even the primary care providers still had extensive training in sleep medicine, making it unclear if all apnea patients would get similar outcomes from their own primary care provider, who might not have this training.

“Also, the studies reviewed were mostly done in obese, middle-aged males with moderate-to-severe apnea,” said Marie-Pierre St-Onge, a researcher at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City who wasn’t involved in the study.

“It is not known if similar results would be seen in patients with more complex cases or low probability for sleep apnea, women, elderly, or those with (other chronic health problems) which are quite prevalent in patients with sleep apnea,” St-Onge said by email.

Still, the results do suggest that it may be possible to get an accurate diagnosis of sleep apnea in primary care, noted Kristen Knutson, a researcher at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago who wasn’t involved in the study.

“If a patient is prescribed treatment for obstructive sleep apnea by a non-specialist and it seems to be working for them, then they probably don’t need to see a specialist,” Knutson said by email. “However, if the treatment does not seem to work well, it is uncomfortable, or they are still sleepy, then that patient could consider a specialist who would have more experience with different treatment options.”

Some patients with a common nighttime breathing disorder known as obstructive sleep apnea may do just as well at managing the condition when they see a primary care provider instead of a specialist, a research review suggests.

“We found that in general, outcomes such as sleepiness, quality of life, and treatment adherence were similar,” said senior study author Dr. Timothy Wilt of the Minneapolis VA Healthcare System and the University of Minnesota School of Medicine.

“Patients with daytime sleepiness could be adequately evaluated and treated by primary care providers who have additional sleep training, especially if access to sleep specialists is limited and if there is unmet demand for sleep apnea services,” Wilt said by email. “However, there is not yet sufficient evidence to support widespread migration of sleep apnea care away from sleep physicians.”

Millions of patients worldwide wear breathing masks all night to ease sleep apnea, a common disorder that leads to disrupted breathing or shallow breaths during sleep. The masks are connected to a machine that provides continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which splints the airway open with an airstream so the upper airway can’t collapse during sleep.

Some patients who can’t tolerate wearing the breathing masks all night may use an alternative apnea treatment known as mandibular advancement devices, which open up space in the airway by pushing out the lower jaw bone to make it less likely that the upper airway collapses during sleep.

Apnea that isn’t properly treated has been linked with excessive daytime sleepiness, decreased quality of life, heart attacks and heart failure, researchers note in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The current study set out to determine if primary care providers who received additional training in diagnosing and treating sleep disorders could manage apnea patients as well as specialists.

Apnea patients cared for by primary care providers had similar outcomes for symptom relief, adherence to prescribed treatments and quality of life as apnea patients seen by specialists, an analysis of 8 previously published studies with a total of 1,515 patients found.

Specialists and primary care providers also appeared to agree on the diagnosis and severity of apnea, an analysis of four smaller studies with a total of 580 patients found.

Researchers rated the quality of the evidence as low, however, and concluded that more studies are still needed to confirm whether some apnea patients could be treated without seeing specialists.

Another limitation of the study is that even the primary care providers still had extensive training in sleep medicine, making it unclear if all apnea patients would get similar outcomes from their own primary care provider, who might not have this training.

“Also, the studies reviewed were mostly done in obese, middle-aged males with moderate-to-severe apnea,” said Marie-Pierre St-Onge, a researcher at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City who wasn’t involved in the study.

“It is not known if similar results would be seen in patients with more complex cases or low probability for sleep apnea, women, elderly, or those with (other chronic health problems) which are quite prevalent in patients with sleep apnea,” St-Onge said by email.

Still, the results do suggest that it may be possible to get an accurate diagnosis of sleep apnea in primary care, noted Kristen Knutson, a researcher at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago who wasn’t involved in the study.

“If a patient is prescribed treatment for obstructive sleep apnea by a non-specialist and it seems to be working for them, then they probably don’t need to see a specialist,” Knutson said by email. “However, if the treatment does not seem to work well, it is uncomfortable, or they are still sleepy, then that patient could consider a specialist who would have more experience with different treatment options.”