Historic buildings in Mosul, including churches and mosques, are being reopened following years of devastation resulting from the Iraqi city’s takeover by the extremist Islamic State (IS) group.

The project, organised and funded by Unesco, began a year after IS was defeated and driven out of the city, in northern Iraq, in 2017.

Unesco’s director-general Audrey Azoulay and Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani are attending a ceremony on Wednesday to mark the reopening.

Local artisans, residents and representatives of all of Mosul’s religious communities will also be there.

In 2014, IS occupied Mosul, which for centuries was seen as a symbol of tolerance and co-existence between different religious and ethnic communities in Iraq.

In 2014, IS occupied Mosul, which for centuries was seen as a symbol of tolerance and co-existence between different religious and ethnic communities in Iraq.

The group imposed its extreme ideology on the city, targeting minorities and killing opponents.

Three years later, a US-backed coalition in alliance with the Iraqi army and state-linked militias mounted an intense ground and air offensive to wrest the city back from IS control. The bloodiest battles focused on the Old City, where the group’s fighters made a last stand.

Mosul photographer Ali al-Baroodi recalls the horror that greeted him when he first entered the area shortly after the street-by-street battle was over in the summer of 2017.

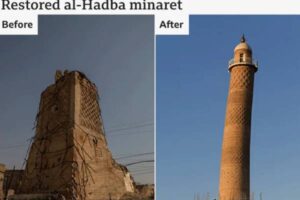

He saw the gloriously skewed al-Hadba minaret, known as the “hunchback”, which had been emblematic of Mosul for hundreds of years, in ruins.

Eighty per cent of the Old City of Mosul, on the west bank of the Tigris, was destroyed during IS’s three-year occupation.

It was not just the churches, mosques and old houses that needed to be repaired, but also the community spirit of those who had lived there for so long in relative harmony between religions and ethnicities.

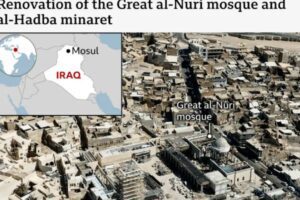

A satellite image shows the location of the mosque and minaret alongside a small map showing Mosul located in the north of Iraq

The huge task of rebuilding began under the auspices of Unesco with a budget of $115m (£93m) that the agency had managed to drum up, much of it from the United Arab Emirates and the European Union.

Father Olivier Poquillon – a Dominican priest – returned to Mosul to help oversee the restoration of one of the key buildings, the convent of Notre-Dame de l’Heure, known locally as al-Saa’a, which was founded nearly 200 years ago.

Father Poquillon says that bringing the communities together was the biggest challenge and the biggest achievement.

In charge of the entire project – which included the restoration of 124 old houses and two especially fine mansions – has been the chief architect Maria Rita Acetoso, who came to Mosul straight from restoration work for Unesco in Afghanistan.

She hopes the reconstruction can restore hope and enable the recovery of people’s cultural identity and memory.

Unesco says tUnesco says that more than 1,300 local young people have been trained up in traditional skills, while some 6,000 new jobs have been created.

More than 100 classrooms were renovated in Mosul. Thousands of historical fragments were recovered and catalogued from the rubble.

Among the host of engineers involved in the rebuilding, 30% were women.

Eight years on, the bells are ringing out again across Mosul from al-Tahera Church, whose roof collapsed after serious damage under IS occupation in 2017.

Other major landmarks of Mosul have also been restored – that wriggling minaret of al-Hadba, the Dominican al-Saa’a Convent and the complex of Al-Nouri mosque.

And people have been able to return to the houses that have been home to their families for centuries.

One resident, Mustafa, said: “My house was built in 1864 – unfortunately it was partly destroyed during the liberation of Mosul and it was unsuitable to live there, especially with my children.

Abdullah’s family has also lived in a house in the Old City since the 19th Century when the area was a centre for the wool trade – which is why he says their home is so precious to them.

The scars of what the people of Mosul endured are yet to heal – just as much of Iraq remains in a fragile state.

But the Old City’s rebirth from the rubble represents hope for a better future – as Ali al-Baroodi continues to document the evolution of his beloved home day by day.